Josef Albers And Mark Rothko

In the vibrant world of modern art, few names stand out as distinctly as Josef Albers and Mark Rothko. Though their artistic styles and philosophies diverged greatly, both left a lasting impact on the evolution of 20th-century abstract painting. Their individual approaches to color, form, and emotional depth helped shape entire movements. Despite their differences, placing Albers and Rothko side by side opens up a compelling discussion on how abstraction, emotion, and perception were interpreted by two visionary artists.

Background and Artistic Foundations

Josef Albers: The Teacher and Color Theorist

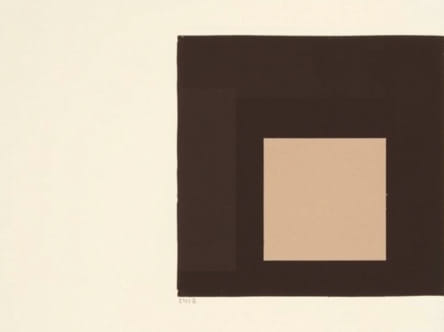

Josef Albers was born in Germany in 1888 and became a prominent figure in the Bauhaus school, where he both studied and taught. His work emphasized order, discipline, and the systematic exploration of color. Albers immigrated to the United States in the 1930s and eventually taught at Black Mountain College and later Yale University. He is best known for his long-running series Homage to the Square, in which he meticulously studied the interaction of color through nested geometric shapes.

Mark Rothko: The Emotional Expressionist

Mark Rothko, on the other hand, was born in Latvia in 1903 and emigrated to the U.S. as a child. He became a key figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Rothko’s art focused on emotional and spiritual resonance. His famous works are large-scale color field paintings, characterized by soft-edged rectangles of luminous color that seem to float on the canvas. He sought to evoke deep emotional reactions from the viewer, exploring the human condition through abstraction.

Philosophies on Art and Expression

Albers’ Rational Approach

Josef Albers viewed art as a structured investigation. His color theory was analytical and grounded in visual perception. He believed that color is not static, but relative; its meaning and impact change based on the colors surrounding it. His methodical paintings aimed to teach viewers how to see, how to understand relationships, and how to think critically about visual experiences.

Rothko’s Spiritual Quest

In stark contrast, Rothko’s work was driven by emotion and existential inquiry. He rejected traditional forms and avoided intellectual explanation. For Rothko, the canvas was a sacred space where viewers could experience profound human emotions like joy, despair, ecstasy, and awe. He often worked in dim light, placing his works close together to create a chapel-like environment for contemplation.

Key Works and Their Significance

Josef Albers: Homage to the Square Series

Albers created hundreds of pieces in this series, each one carefully planned to explore the relationship between colors. Using only squares arranged concentrically, he demonstrated how colors influence one another visually. Each painting was an experiment, showing how our perception of a single color shifts depending on its context. His work continues to be used in educational settings as a foundation for teaching color theory.

Mark Rothko: Seagram Murals and Beyond

Among Rothko’s most renowned works are the Seagram Murals, originally commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York. However, Rothko later withdrew from the project, feeling that the setting would diminish the impact of the paintings. These dark, brooding canvases marked a shift in Rothko’s style, moving toward somber tones and introspective themes. His later works became increasingly meditative, culminating in the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas a space that invites reflection through a series of dark, enveloping panels.

Interaction and Tension Between Their Styles

Divergent Ideologies in Modernism

Albers and Rothko inhabited different corners of the modern art world. Albers’ alignment with the Bauhaus and formalist traditions placed him in the realm of intellectual, pedagogical art. Rothko, aligned with Abstract Expressionism, rejected rationalism in favor of emotional authenticity. This difference illustrates a key tension within modernism: the push and pull between reason and emotion, order and chaos, structure and spontaneity.

Reception by Audiences and Critics

While both artists achieved significant acclaim, they appealed to different audiences. Albers was beloved by educators, designers, and those who valued theory and visual logic. Rothko captured the imagination of those seeking depth, meaning, and emotional catharsis. Critics often contrasted their styles, with some viewing Albers as cold and Rothko as too sentimental. Yet over time, both gained respect for their unique contributions to the understanding of color and abstraction.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

Albers’ Influence in Education

Albers’ book,Interaction of Color, remains a foundational text in design and art schools. His teaching methods encouraged experimentation and perception-based learning. Through his disciplined approach, Albers influenced generations of artists, designers, and thinkers who continue to explore the subtleties of color relationships today.

Rothko’s Enduring Spiritual Presence

Rothko’s works continue to inspire emotional reactions worldwide. Museums often display his paintings in quiet, meditative rooms to preserve the immersive experience he envisioned. His commitment to emotional truth and his refusal to commercialize his art have made him a revered figure in art history. The Rothko Chapel, in particular, stands as a monument to the power of abstract art to convey the deepest layers of human experience.

The careers of Josef Albers and Mark Rothko offer a fascinating study in contrast. Albers, the intellectual color theorist, used strict forms to explore visual perception. Rothko, the emotional mystic, sought to stir the soul through glowing rectangles of color. Their distinct approaches reveal the breadth of abstraction as a mode of expression ranging from the analytical to the spiritual. When viewed together, their works enrich our understanding of how color, form, and intent can shape human experience through art. Despite their differences, both artists remind us that the language of abstraction has many dialects, each powerful in its own right.